We’ve all seen him. He’s broody, misunderstood, and usually comes from a broken home. The leather jacket, beat-up motorcycle, and James Dean bravado are optional. The trope of the ‘Bad Boy’ has been embedded in our cultural subconscious for generations; regardless of what form he comes in, we can still recognize him. The bad boy is so classic that his characteristics can change without forfeiting their purpose.

However, we’ve been experiencing a shift in the ways in which women and femmes tolerate mistreatment by men. There are dozens of think-pieces like this one from Bolde about “bare minimum” men, which explores that the idea that women are supposed to praise men who do the bare minimum in regards to relationships and sex is becoming a thing of the past.

The bad boy is a beloved trope, in part because each generation has one that defines their adolescence. In tracking the evolution of the bad boy, it may be possible to figure out whether or not he’s still meaningful to our culture.

In a time of women speaking up about bare minimum men and owning their worth, is the bad boy trope still culturally relevant, or is he a relic from another era?

The bad boys of old

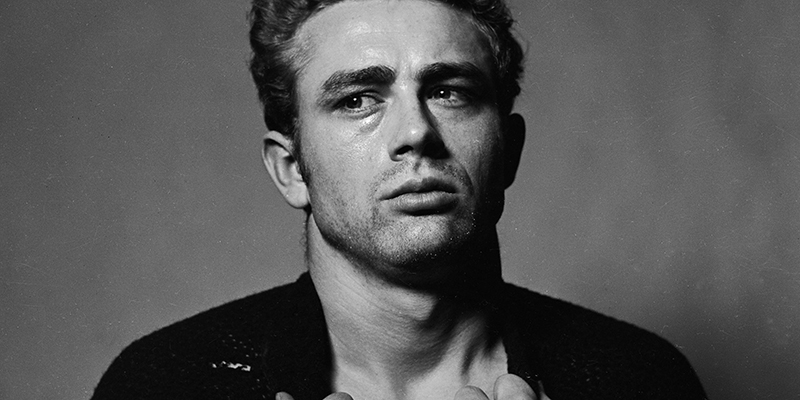

The first popular instance of the bad boy trope occurred in 1955, with the theatrical release of Rebel Without A Cause. One of the first major films for and about teenagers, Rebel Without A Cause established the bad boy trope through James Dean’s Jim Stark, a troubled adolescent with a knack for petty crime and a casualty of an estranged relationship with his parents. The idea of a “teenager” was not as popular at the time, in part because there weren’t any specific cultural markings of an adolescent in the way that there are today.

Jim Stark’s bad boy has been recreated to some extent in plenty of ways: the clothes, the relationship with his parents, the emotional damage. And it’s clear the bad boy is certainly a product of the shifting cultural paradigm of the 1950s and the popularization of teenagers as a unique group of people.

Fast-forward some decades and Dylan McKay arrived on television screens around the country on October 11, 1990, as the broody, misunderstood foil of many of the other male characters in Beverly Hills, 90210. Portrayed by the late Luke Perry, Dylan was at the time, and arguably still is, the quintessential bad boy of television.

Although he has the tough exterior, the bad relationship with his parents, the looks, there’s something else to the character that makes him unforgettable, even in today’s overcrowded media landscape. Even beneath the messiness of the character and his tumultuous relationships throughout the run of the show, Dylan is empathetic and at times, magical. Following the news of Perry’s death on March 4th, a large number of op-eds about Perry and his portrayal of Dylan as a bad boy with a heart of gold followed. Nearly 30 years after his first appearance on the show, Dylan McKay remains an important representation of this trope.

Modern takes

As we enter the supposed “Golden Age of Television”, we begin to see a new kind of bad boy. While the characteristics are the same, the costume is often not. Degrassi: The Next Generation, the spin-off of the original Degrassi franchise series in the late 80s and early 90s, ran for 14 seasons and contained several different interpretations of the bad boy trope.

Sean Cameron lived with his brother in a trailer, wore a wife beater to school, and eventually went to jail. Craig Manning is an abuse victim, who gets an underclassman pregnant and eventually starts a band in his foster father’s basement. Later in the series, Eli Goldsworthy drove a hearse, wore eyeliner, and directed a school play about his breakup. While each depiction is different and more melodramatic than the one before it, each of them also became fan-favorites in part because of their appeal to female viewers.

As teen dramas of the early aughts flourished, we saw more variety in the bad boy trope. Gossip Girl introduced Chuck Bass, who appealed to audiences not only because of his bad boy image but because of his lavish life as well. However, he does appear to be worse than the other bad boys in terms of attitude (he attempts to rape a fourteen-year-old girl in the pilot episode). Even though his character is a predator, audiences flock to his defense.

This presents a new aspect of the trope: as television has gotten grittier and more aggressively sexual, so has its characters.

Most recently, Netflix’s On My Block tells the story of a group of teenagers living in gang territory in Los Angeles, desperate to save their friend from his family’s gang affiliation. Cesar Diaz is fourteen, incredibly smart, and has dreams of college alongside his close-knit friend group. He is eventually forced to join the gang—the Santos—after his brother is released from prison early. Cesar is a new spin on the classic trope—while he has the costume and the attitude, he’s more sunny than broody. He’s a challenge to the misconception of gang life.

Cesar Diaz has the potential to be the Dylan McKay of his generation. In an age of television that is increasingly angry and dark, both character’s use vulnerability as a coping mechanism. They, like many of the other characters within this trope, are loved by audiences because of their glimpses of vulnerability, the ways in which they break away from traditional masculinity.

A relic or an enduring classic?

While the bad boy certainly hit its peak, its cultural power lies in its ability to shift without losing his meaning.

It may be possible that the recent emphasis on “bare minimum” men may have an impact on this classic trope. If we start demanding more from our male characters than machismo and brooding, we may start to see more multifaceted characters who use challenge the status quo and use their vulnerability as a strength rather than a weakness.