In part one of our dive into the rise and fall of arena rock, we took a hard look at the arena rock phenomenon in the context of rock and roll history and discussed whether arena rock is truly dead, or if it lives on in another form. Now in part two we’re diving a little deeper to figure out why this even happened. So to kick things off, we’re going to start with one super important question:

Is hip-hop the new rock and roll?

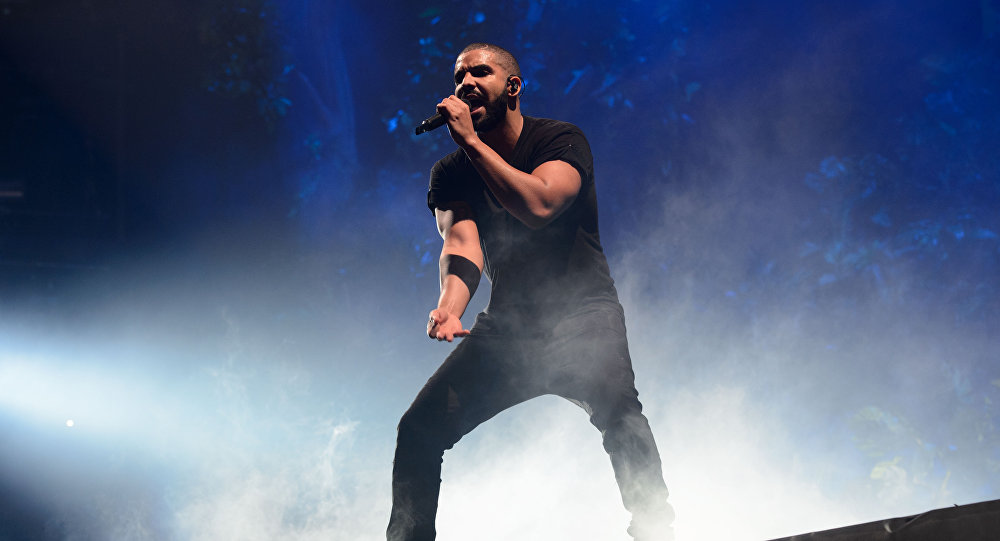

Rock and roll is “a countercultural, anti-establishment, in-your-face social movement that inspired a generation of teenagers and vexed their parents“. With that in mind, today it is rappers like Drake, Kanye West⏤bar his MAGA shenanigans⏤and Kendrick Lamar that are energizing teenagers with their attitude and creating music that makes their parents nauseous. This is a rock and roll trait modernized. Moreover, it is these household names that are filling arenas the world over; there is no doubt that hip-hop has taken over rock.

According to Nielsen’s 2017 year-end report, hip-hop surpassed rock as the most dominant genre for the first time ever. In the same report, eight of the top ten artists of the year came from the hip-hop/R&B genre. Given hip-hop’s mainstream dominance for the last decade, the only surprise is that 2017 was the year rock first lost its throne.

Another example of the rise of hip-hop is the recent Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductions. In 2007, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious were the first rap act to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Then came Run-DMC in 2009, The Beastie Boys in 2012, Public Enemy in 2013, N.W.A. in 2016, and Tupac Shakur in 2017. The decision to induct N.W.A. in 2016 received public backlash, most notably from KISS frontman, Gene Simmons.

Ice Cube of N.W.A. made his position clear on accepting the award: “Are we rock & roll?” he asked. “I say, ‘You goddamn right, we rock & roll.’ Rock & roll is not an instrument; rock & roll is not even a style of music. Rock & roll is a spirit. It’s a spirit. It’s been going since the blues, jazz, bebop, soul, R&B, rock & roll, heavy metal, punk rock and yes, hip-hop. . . Rock & roll is not conforming to the people who came before you, but creating your own path in music and in life. That is rock & roll, and that is us.”

In response, Simmons Tweeted: “Respectfully, let me know when Jimi Hendrix gets into the Hip-Hop Hall of Fame, then you’ll have a point.” Cube replied, stating “We invent it. Y’all reprint it”, alluding to the African-American origins of rock and roll. Simmons replied, “[I] respect N.W.A, but when Led Zep gets into Rap Hall of Fame, I will agree with your point.”

Both Simmons and Cube raise important points. Should the definition of rock and roll be all-inclusive? Does hip-hop’s R&B heritage amount to such an inclusion? Cube’s initial remarks highlight rock and roll as a social movement that takes on many musical forms. In the same line of thinking, there is certainly an argument to be made for the acknowledgement of hip-hop as a form and derivative of rock and roll. One could argue that rock and roll is: (i) a musical genre rooted in time; (ii) a musical genre rooted in style; and (iii) a social movement rooted in certain aesthetic and social ideologies. One could also argue that rock music today is less rock and roll than hip-hop. We will return to this topic at the end of part three.

Headliners

Another telltale sign of hip-hop’s rise and rock’s demise is the change in artists headlining major festivals, including Glastonbury and Coachella. For instance, 2018 saw a Coachella lineup with no rock headliner for the first time in its 19-year history. The trend is clear; there is a decline in the influence and reach of rock in the mainstream domain. In addition, whilst many hip-hop artists are relatively new onto the scene, top rock artists that feature at the same level have often been around for a while and there are less new rock artists making it to the same level as new hip-hop artists.

Rock is tending towards reverence of the past, as is seen with Netflix’s Mötley Crüe biopic The Dirt. The result sometimes comes across as an outdated pastiche and not the real thing. This sterility is reflected also in its ageing audience that often resembles something more akin to a family day out than an adrenaline-fuelled house party. The ‘live fast, die young’ mantra becomes less and less pertinent as the years go on⏤today, the phrase is far more suited to hip-hop culture.

The indie-fatigable revolution

Whilst arena rock was enjoying its time in the spotlight, the musical underworld was undergoing a paradigm shift that would soon have a big impact on arena rock. Here’s for another potted history.

Starting in the late 1970s, the indie revolution began to take shape in the United Kingdom and the United States, and broke into the mainstream scene in the 1990s. The term ‘indie’ had been coined after the great swathe of independent record labels that produced the music. The term soon became interchangeable with ‘alternative’, defining the underground nature of the music. However, as the movement progressed, fewer and fewer indie labels were truly independent, and many powerhouses such as Sony and Columbia produced so-called indie music⏤it has even been suggested that independent labels now have a bigger combined market share than any major label. As with arena rock, there exists a duality between the indie movement and genre.

The indie of the mid-1980s was dominated by bands including The Smiths in the UK and R.E.M. in the US. By the 1990s, the term loosened further to encompass grunge, Britpop, and pop punk to name but a few. Indie reached its peak in the 2000s, with the commercial success of bands such as Interpol and The Strokes. However, this newfound success led to critical questions about the aptness of the term given that it was neither independent nor alternative. The movement appeared to benefit from its being both alternative and mainstream.

So, how did the indie revolution impact arena rock? The proliferation of independent labels meant that for every commercially dominant artist, there were 1,000 smaller artists fighting for the same bandwidth. Sure, the arena rockers were still the big fish, but these smaller fish formed resilient subcultures and had the benefit of their wide-arching, colonial umbrella term under which to progress, akin to the Portuguese Man-of-War. When subcultures grew into viable genres including grunge, Britpop, and pop punk, it was considered a win for indie. When artists including Kings of Leon, The Killers, and Kasabian became commercially successful in the 2000s, it was also a win for indie. Even when artists including Coldplay and Maroon 5 ‘sold out’, their successes were considered a win for indie.

The passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 had a global impact on the way in which media is distributed and consumed, threatening monopolization and homogenization of news and media outlets, making the fight for commercial success greater than ever. The fact that indie survived this socio-political development a testament to the power of the movement, made possible within the music industry’s new commercial model of the Internet Age.

The impact of the Internet

The Internet changed the way music would be made, distributed, accessed, and listened to like no other single development. With the Internet came the democratization of music production software and access to music through open source software and, eventually, streaming services such as YouTube and Spotify. The former meant that near enough anyone with a computer could start making music in their own bedroom, giving the layperson more tools at their fingertips than producers of decades gone by could ever have wished for. The latter meant that the music industry was becoming ever more on-demand, giving the general public the power to listen to what they wanted when they wanted.

The rise of on-demand music developed in tandem with the indie revolution, and the pair were a match made in heaven. The Internet was the perfect gateway for the wannabe pop star and producer; for every band trying to make it, there was an indie label looking to make a name for itself. Moreover, artists could simply produce their own work and release it online. Granted, not everyone made it, but whatever did make it was considered a win for indie and for the Internet Age.

This new commercial model also meant that fans were free to explore their interests rather than rely on charts, radio stations, local record stores. This, in turn, facilitated the rise of subcultures, both online and in the physical world. In their book Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual, Andy Bennett and Richard A. Peterson describe the phenomenon of ‘virtual scenes‘ that is a product of the Internet:

“In this age of electronic communication, fan clubs dedicated to specific artists, groups, and subgenres have proliferated by using the Internet to communicate with each other.”

Thus, as the commercial powerhouses fought to retain their bandwidth monopoly, the Internet made non-mainstream success more sustainable than ever, pleasing both artists and fans alike. This phenomenon, and the Internet as a whole, had a direct impact on the fate of arena rock and every other musical form under the sun.

Woah, we’re halfway there. . .

In the final installment of this three-part special, soon to come, we’ll consider the decline of blues elements, the proliferation of music production software, and what the future may hold for rock and roll and arena rock as musical and cultural movements.

Until next time…